I got through thirty-one books this year, not including those I read as judge in the Aurealis Awards. Still, less than I would have liked. I try – and usually succeed – to write every day. But as an author, it is just as important to read every day, and in this, I’ve allowed myself to be distracted. We are surrounded by so many high-endorphin activities – almost all of which involve a screen – that it can be difficult to pull away from this addiction to something with a lower endorphin reward, but far greater intrinsic value.

Speaking of, my favourite TV shows of the year were: Mr In-Between (Australian), Mare of East Town (American), The Expanse (American), Hemingway (Documentary – American), Black Summer (Season 2) (American), Squid Game (South Korean), and To The Lake (Russian). Mr. In-Between was my favourite, a blackly comic Australia noir about hitman Ray Shoesmith. All 3 seasons are excellent.

My favourite movies were: Free Guy (American), Pig (American), Paper Tigers (American), Blue Ruin (American), Destroyer (American), 1917 (British), Calibre (British) and Riders of Justice (Danish). Pig was my movie of the year. A quietly moving and melancholic film, featuring a restrained and powerful performance by Nick Cage. Kidman was excellent in the neo-noir, Destroyer, and I laughed way more than I should have during Free Guy. I’ve yet to see Dune.

Books. I try to read outside the US wherever possible. Such is the cultural dominance of America in Australia that it takes a dedicated and conscious effort to read works from the rest of the world. I didn’t read as much East Asian literature as I normally do in 2021, but read way more contemporary novels. Next year I have a vague plan to read some South Asian literature (of which I’ve read almost none), whatever I can on Macau (research for a novel), and more local authors. But I always, always cheat on my to-read pile (I’m an unfaithful bastard), so we shall see.

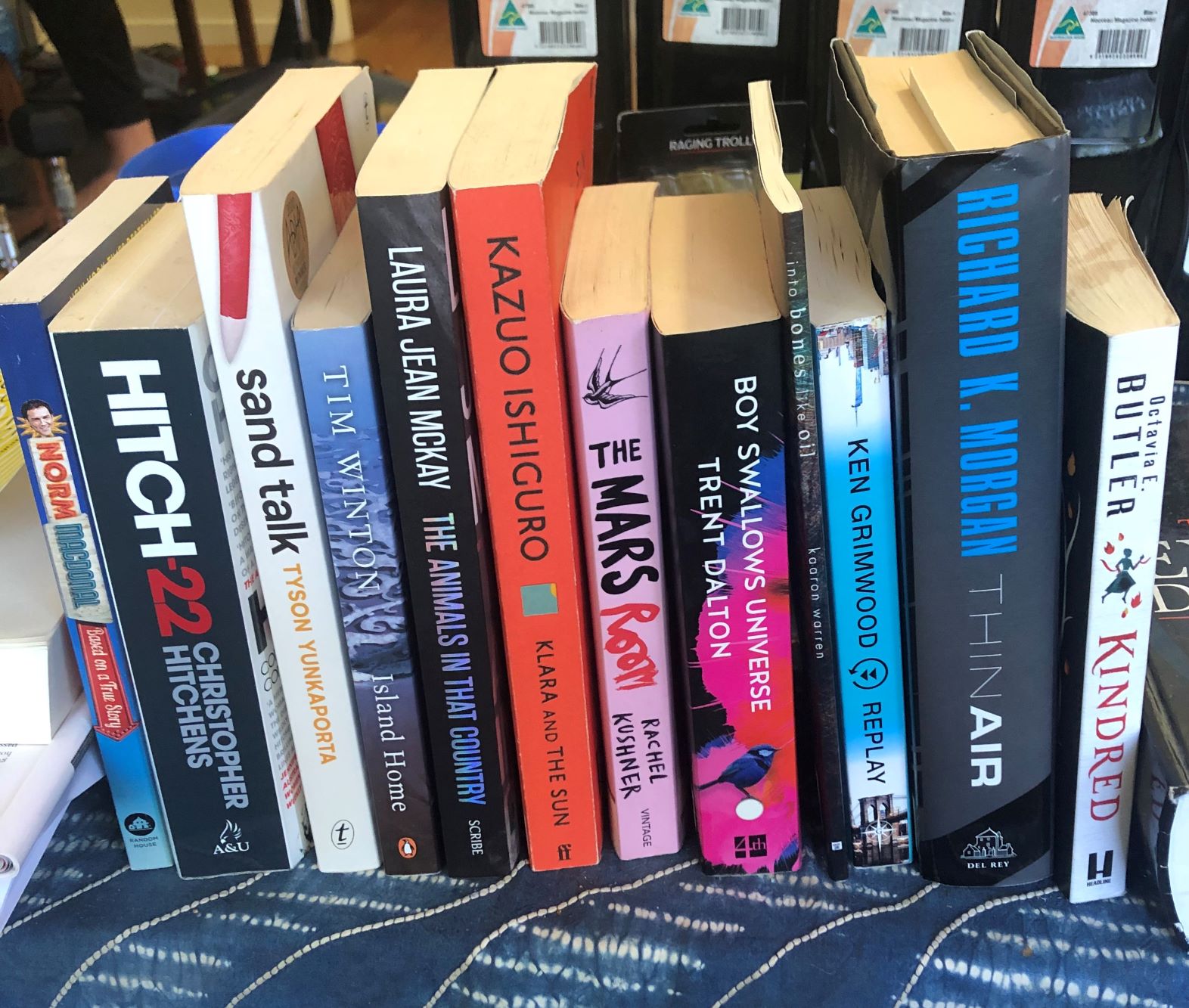

In no particular order, my favourite books of the year:

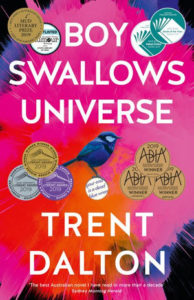

Boy Swallows Universe (2018), by Trent Dalton (Australian)

Superb debut novel from former journalist Trent Dalton. It’s about a working class boy growing up in extremely difficult circumstances. His mum is a former addict, his step-father – though a good bloke – is also a low-level heroin dealer, and his blood father an alcoholic. It depicts working class Australia just the way it is: tough, multicultural, unforgiving of weakness. It seemed while I was reading that the author knew what he was talking about, and I later discovered that the book was based on experiences from the author’s life. It won just about every literary award in Australia, and deservedly so.

Despite the subject matter, it is an unashamedly commercial work. And so what? It’s a great Australian novel.

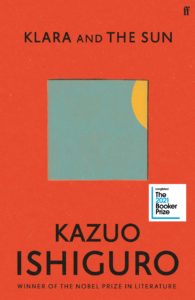

Klara and the Sun (2021), by Kazuo Ishiguro (British)

Ishiguro is my favourite living author, and once again he does not disappoint. Klara and the Sun is an excellent science fiction novel, concerned with Ishiguro’s career-long obsessions over loyalty, individual agency, and loss. The protagonist is Klara, a solar-powered artificial intelligence, who is sold into service of a family to help with their sickly daughter, Josie. The daughter became ill after her parents had her ‘lifted’ – genetically enhanced, with the promise of being academically superior.

Klara is highly intelligent, yet has a child-like innocence about the world. Her true purpose in life is to serve (much like the Butler Stevens in Remains of the Day), but her fate is to be discarded, much like the young people in Never Let Me Go.

Ishiguro does a remarkable job in portraying the mind of an artificial intelligence. The insights they might have into human behaviour, alongside their deep confusion; the way they might see and process the world, the way they react to stress. It is hard for any writer to deliver a world-view that is alien and disorienting to our own, and yet stays believable and accessible to the reader. As I said: Ishiguro delivers. He even explores the idea of AI spirituality (or superstition), and ingeniously constructs a believable cosmology for an android who relies on the power of the sun.

It is a beautiful novel, with a heartbreaking ending.

Hitch-22 (2010), by Christopher Hitchens (British/American)

Christopher Hitchens is not someone I always agree with (who could?), but someone whose erudition and courage I always admired. His memoir showcases his wit, mastery of the English language, his knowledge of history – in particular religious history – and more than anything, a life lived to the fullest.

language, his knowledge of history – in particular religious history – and more than anything, a life lived to the fullest.

Whether being spanked on the butt by Margaret Thatcher (who called him a ‘naughty boy’); sleeping with anyone, male or female, as a young and handsome activist; dishing the dirt on Clinton (whom he knew at Oxford); stoutly defending Salman Rushdie and free speech against religious fascism; or reflecting on the nature of life and death, he is eminently readable.

One of the interesting aspects of the memoir was the insight it gave into Hitchens’ backing for the Iraq War. He had an avowedly progressive stance on most issues – particularly earlier in life – and so I never quite understood his full-throated support for that disastrous intervention. Here he explains his thought process – which I cannot do justice here – but which began with him being one of those who criticised Bush Snr for not removing Saddam in Gulf War I (as many progressives did at the time). His logic for the second invasion flowed from this. I disagree with him still, and think that ironically, for an avowed atheist, he must have truly believed in miracles if he thought Iraq was not going to descend into the post-invasion mess that it did.

But agree or disagree, this is a memoir worth reading.

The Mars Room (2018), by Rachel Kushner (American)

Sometimes I’ll be reading a novel with multiple and seemingly unrelated plot strands and I’ll think: the author can’t possibly pull this all together by the end. Then, of course, they do, and you’ll see how it was possible all along, see how it couldn’t have happened any other way. Strangely, for such a well-received book, The Mars Room does not bring it all together in a satisfying way.

So why include it in my best of the year? I found it un-put-downable. I rarely experience this with novels these days – especially the so-called ‘literary’ novels – but The Mars Room took me to a place I’d never been (a women’s prison in the US), and the journey was immersive and believable.

Island Home (2015), by Tim Winton (Australian)

A series of collected essays interspersed with new material written for the book, Winton calls this a ‘landscape memoir’. It’s clear why: the author has a love of the Australian wilderness, and moreover a deep understanding of it. Tim Winton touches on questions of identity in an era where Australian identity can sometimes feels swamped with American culture, American ways of thinking, and American ways of being. He delves into an issue that I’ve often thought about – that our landscape and natural environment can save us.

It can save us literarily, because we live here after all, and it helps if it is habitable. Winton reminds us that we must act as custodians of this vast, often terrifying, yet ultimately fragile land. It can also save us spiritually, as by becoming closer to it, we understand its stories and its character and through these, our own.

If you are an Australian who wants to better understand yourself, or a foreigner who wants to better understand my country, this is well worth a read.

Sand Talk (2019), by Tyson Yunkaporta (Australian)

Works that discuss Indigenous history in Australia can often be fraught and simplistic, with one side or the other trying to ‘prove’ a particular world view with bombastic and unsophisticated invective. Tyson, rather, is modest and self-effacing, all the while offering a new way of thinking about time, culture, and knowledge. He wants to yarn with us: have a conversation.

He helped me to think about a number of things different ways, including, for example, breaking down the dichotomy of ‘indigenous’ and ‘non-indigenous.’ He yarns with native peoples throughout the world, from Australia through to Scandinavia. Causing him, and the reader, to reflect on how the world ‘indigenous’ has been used by colonisers to split the world into two camps, rather than to imagine and engage with a far more complex reality. As he says: “black and white is a limiting paradigm for understanding the Indigenous experience.”

He also has a wicked sense of humour. His story about a Marxist writer from early settler history, who was so oppressed she had to move to one of her other properties, made me laugh out loud.

Unfortunately, Tyson does lapse into some crude dichotomies about two-thirds of the way through the book, even while decrying the simplification of complex issues. But as his approach throughout is one of dialogue, discovery, and one of invitation: for all of us to try to engage with the world of Indigenous reasoning and philosophy, these flaws should be overlooked. In fact, Tyson wants us to disagree with him: “In the end nobody can stop dialogue, because it is a force of nature.”

Honourable Mentions

All of these were excellent. They could all easily have been included in my straight-up favourites for the year:

Thin Air (2018), by Richard Morgan (British)

An ex-corporate enforcer, Hakan Veil, is forced to bodyguard Madison Madekwe, part of a colonial audit team investigating a disappeared lottery winner on Mars. Morgan proved himself to be one of the most important contemporary cyberpunk authors with his debut, Altered Carbon, and he showcases is mastery of the sub-genre in his most recent novel.

The Animals in that Country (2020), by Laura Jean McKay (Australian)

Laura’s novel either won or was nominated for just about everything. It won the prestigious Arthur C Clarke, the Australian Aurealis for best Novel, and the Victorian Prize for Literature, among others. It wasn’t nominated for a Hugo, of course, and didn’t even make the longlist, because the ‘World’ Science Fiction Awards almost never include anyone from the world outside the United States.

Jean is a hard-drinking, foul-mouthed grandmother, and assistant at a Zoo. When a virus makes humans able to communicate with animals, society falls apart. Laura’s imaginative leap – in exploring the bizarre language of animals (through smells, movements, noises) – is an extraordinary piece of world-building.

Based on a True Story (2016), by Norm MacDonald (Canadian)

Norm MacDonald died this year, and as he is a comedian I’ve always thought was very funny, I sought out his kinda-sorta-memoir.

It was surprisingly good. Macdonald stuffs it with jokes and tall tales and one liners, but underneath it all there is clearly a well-read, highly intelligent man. One of the chapters involves him going to a child’s funeral – the writing here remarkable, the mood created tragic. A funny book that offers acute observations into the meaning of our lives.

Exhalation (2019), by Ted Chiang (American)

Sacrilegious to say, but I didn’t love this the way I did his first collection, Stories of Your Life and Others. But in the end, he is Ted-fucking-Chiang, so he makes the list. The final story ‘Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom,’ was, in my view, the best.

Kindred (1979), by Octavia Butler (American)

This is the first book I’ve read by Butler, but here she proves to be both a courageous and nuanced author. Kindred is a time-travel story about an African-American woman (Dana), who keeps being pulled back in time to help protect her (white, slave-owning) ancestor in the antebellum south circa 1815. I don’t always enjoy the so-called classics of SF, but I admired this.

Into Bones Like Oil (2019), by Kaaron Warren (Australian)

I don’t read much horror at all, but I am glad I read this by local author and friend, Kaaron Warren. Kaaron has an uncanny eye for human detail, and an ability to induce creeping dread in the reader.

Replay (1986), by Ken Grimwood (American)

I started reading Replay on Christmas day (we have very quiet and relaxed Christmases in our house). I finished it the same day. Replay has a great hook – the protagonist, Jeff, has a heart attack at the age of 43, dies, and wakes up in his 18-year old body. He lives his life, profiting enormously from his foreknowledge – and dies again at 43, transporting back to his teenage self. A cycle of 25 years, repeated over and over. It’s entertaining, eminently readable, and makes you reflect on how we spend what little time we have here on Earth.