A staple of noir cinema is the heist gone wrong. Perhaps the best known contemporary example is Reservoir Dogs (1992), in which Tarantino – steeped in and heavily influence by classic noir – depicts the aftermath of a diamond robbery turned clusterfuck. Tarantino, riffing on the noir penchant for superb  dialogue, also gave us the lengthy, quotable scene wherein the characters discuss social mores or popular culture. In case of Reservoir Dogs, cold opening the film with a breakfast diner discussion on Madonna’s ‘Like a Virgin’ and whether the song is really about a fucking a guy with a really big dick.

dialogue, also gave us the lengthy, quotable scene wherein the characters discuss social mores or popular culture. In case of Reservoir Dogs, cold opening the film with a breakfast diner discussion on Madonna’s ‘Like a Virgin’ and whether the song is really about a fucking a guy with a really big dick.

(click PDF icon, upper right, if you prefer to read black-on-white)

Tarantino draws on a storied history of the failed caper, going back to Criss Cross (1949) The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and The Killing (1956) (A Kubrick film which influenced Reservoir Dogs)

The newly-released Baby Driver continues this tradition, according to many critics, who have dubbed it noir. Without doubt the film deals with many of the classic noir clichés that tend to accompany the heist gone wrong: the  unreliable and violent crew gathered to pull off the score, the omnipresent crime boss who threatens loved ones with unspeakable acts, the crook who wants to get out of the business after the next score.

unreliable and violent crew gathered to pull off the score, the omnipresent crime boss who threatens loved ones with unspeakable acts, the crook who wants to get out of the business after the next score.

And save a problematic third act (where Jon Hamm becomes the Terminator, and the ruthless crime lord discovers a heart of gold), Baby Driver is a damn good film. But whether it qualifies as noir is a separate question.

The Thief (1981) by Michael Mann, starring James Caan, is unquestionably a neo-noir. Caan (Frank) wants to do one more big job (noir trope tick), so he can leave the business and live happily ever after with the new love of his life Jessie (tick), but gets entangled with a ruthless crime boss who changes the terms of the deal (tick), threatens his family (tick), and kills his close friend in order to emphasise the point (and tick).

Yet, despite all the predictable tropes, and a pure 80s synthesiser score, The Thief ratchets up the tension from the opening and never lets go. One of the key ways it does this – and perhaps the most important way it differs from Baby Driver – is the sense of foreboding. In The Thief, you never know if Frank is going to escape alive, or whether his family will remain unharmed. The viewer genuinely fears for the characters.

This also how Baby Driver departs from noir – there’s no sense of impending, unavoidable tragedy. George RR Martin (his work is called ‘Grimdark’ which is merely another name for fantasy noir) has said a willingness to kill characters is necessary in order for the reader to feel fear, to never know how things are going to turn out. This never happens in Baby Driver. I never once believed the protagonist (‘Baby’) was going to have his head – or pecker – cut off. But The Thief, on the other hand, had me pleading with Frank to get out – get out! – before it was too late.

The Thief has an extended dialogue-in-a-diner scene between Frank and Jessie every bit as compelling as anything Tarantino has written. But unlike the funny, coarse, quotable Tarantino experience, the protagonist Frank quietly tells Jessie about his time in jail. How stealing 40 dollars turned into an 11 year sentence. Because jail was place he was forced to kill to stop being raped and killed, and implies terrible things happened to him anyway. It’s an extraordinary, edge-of-the seat monologue detailing the brutal life of the con and the dehumanising consequences of the prison system.

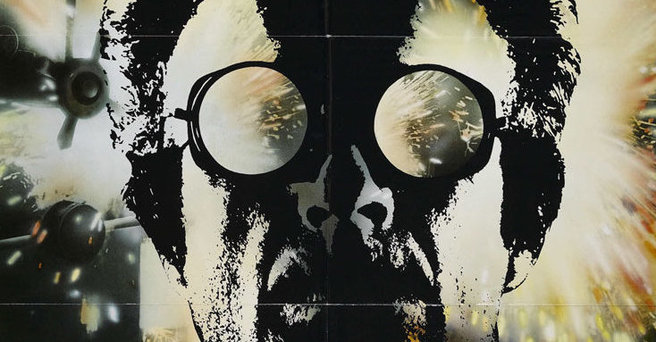

In the final heist, Caan and two others (including James Belushi, giving maybe the only decent performance of his entire career) crack a giant safe using an thermal lance (see picture). There’s no special effects; you  know they are actually melting solid steel. It’s weird and strangely exhilarating watching something with zero CGI – the heat in the room, the fumes, the stress of the work, all seem real because they are real.

know they are actually melting solid steel. It’s weird and strangely exhilarating watching something with zero CGI – the heat in the room, the fumes, the stress of the work, all seem real because they are real.

They succeed, but of course the mafia boss that hired Frank changes the terms of the deal. In a contemporary world where we’ve seen The Sopranos, and Casino and Goodfellas, where we’ve watched every possible way some chump can be threatened, intimidated, tortured, or otherwise bent to the will of the cosa nostra; despite all of this, the threats delivered to Frank by the boss are chilling. Just words, not a toe-cutter or vice to be seen, just words, but they work. I can only imagine how audiences would have reacted forty years ago.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), another classic neo-noir is, if anything, less sentimental than The Thief. With a largely irredeemable petty crim as the titular character, Robert Mitchum plays to perfection the washed up, tired and aging crook. It’s based on a novel written by George V Higgins, whose superlative ability at dialogue shines in the film.

Eddie Coyle lives an unglamorous life. Small apartment, three children and a wife. In a welcome twist, his wife is an equally unglamorous Irish who he still loves dearly, as with his children.

The heist that goes wrong isn’t Eddie Coyle’s, but his friends’. But it is Eddie who wears the consequences. The men he supplies with guns for the bank robberies get ratted on and caught, yet Eddie is pinned as the informer. Like The Thief, the tension is maintained throughout. I was never quite sure how the various story strands were going to be resolved, or whether Coyle was going to live.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle is the polar opposite of Baby Driver. There is a car chase, but it is brief and brutal. Baby is at the start of a criminal career, one he was forced into. Eddie Coyle is at the end of a career, one he chose, and under no illusions that he is ever going to get ‘out’ of it. There’s no beautiful girls, no open road of possibility, no chance of redemption just around the corner. The only hope he has is to turn informant in order to avoid a prison sentence, while continuing a life of petty crime.

Baby Driver is fun, the car chases are exciting, the music heart pumping. It’s funny, too – I loved the scene where the Baby meets a crim with ‘hate’ tattooed on his neck, though the E is covered over with a love heart. When Baby asks why he covered the E, he says:

“To help me get a job.”

“How’s that working out for you?”

“Who doesn’t love hats?”

While Baby Driver deals in noir tropes, it doesn’t deliver noir consequences. Loves ones are left alone, the unreliable partners all get their comeuppance.

Baby does do time in prison at the end, which was a surprising way to end the movie. But he doesn’t do time in noir universe of Frank or Eddie Coyle – not the Darwinian, brutalising experience of a real prison. Rather, Baby quickly gets promoted to a variety of prison jobs via movie montage, and emerges five years later to the girl of his dreams, waiting aside a sweet ride.

That’s nice; I liked it. But it ain’t noir.