I was a few days into writing my first time travel story when I realised I was screwed.

After a particularly difficult session involving much grinding of teeth trying as I tried to figure out the implications of time-travel on the protagonist, I tweeted something along the lines of: “gee time travel is hard to write.”

Someone helpfully answered with: “If you’re using six-dimensional time you don’t have to worry about the Grandfather Paradox.”

To which my reaction was: holy fuckballs – six dimensions? I find it difficult writing characters in more than one. And when anyone starts using the word paradox you know there is going to be trouble.

So I downed tools and switched to research. The eye-glazingly complex physics of time-travel is always best illuminated by science fiction, of course.

Back to the Future (I-III)

I watched these again as part of my ‘research’ (writing is seriously the greatest gig). The first is still a clever, fun film. The second’s not bad – if somewhat self-indulgent – the third tedious and repetitive.

I watched these again as part of my ‘research’ (writing is seriously the greatest gig). The first is still a clever, fun film. The second’s not bad – if somewhat self-indulgent – the third tedious and repetitive.

The laws of time-travel in Back to the Future are 1) time is changeable, and 2) this creates alternate timelines.

So when Marty gets trapped back in 1955, he accidentally prevents an incident occurring wherein his father meets his mother (by getting hit by a car driven by his future grandfather, rather than his father being hit by the car). So not only must he work with Doc to get himself back to the future, he must ensure his parents get together. A picture Marty has of his siblings shows them disappearing as the chances of his father and mother marrying decrease.

Fortunately, Marty facilitates his father wooing his mother, lighting strikes the DeLorean at the exact right moment, and Marty goes back to the future. All his problems are solved.

Logic Problems:

Or are they?

The logical flaws arise when Marty McFly returns home. He has created an alternate timeline with his actions, not only ensuring his mother and father meet, but that his father becomes more confident and successful, and his family in general prospers. Sure, a rather satisfying conclusion for the audience: the bully gets his comeuppance, the downtrodden triumph.

However, the problem is that Marty from the original timeline (the one the audience sees) has no memory of his childhood from the new timeline created. When he returns, he is stunned to see how successful his family is, remembering only the way things were.

The big question: what happened to Marty II? It seems he is wiped out of existence (because he surely existed in the new timeline).

By the franchise’s own laws of time travel (established by Doc in Back to the Future II) Marty II should still exist (they meet alternate versions of themselves often throughout the three films) and Marty I would never be able to go back to an unchanged timeline. Via the internal logic of BTTF, any time travel leaves the traveller marooned, a temporal exile (with the possible exception of time travel where one simply observes and never interacts in any way with the original timeline).

Back to the Future was, as such, missing Marty II.

Some other interesting logical problems documented here at the den of geek.

Looper

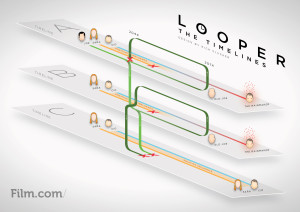

The Looper time rules are much like those of Back to the Future – timelines are changeable. Travelling back in time and doing something to the younger self will have an impact on the future self. Looper takes this even further, by having memories change as well. So as Old Joe (Bruce Willis) watches his younger self (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) do things that will change his personal history, his memories alter and begin to overlap. The two timelines become superimposed in memory.

The Looper time rules are much like those of Back to the Future – timelines are changeable. Travelling back in time and doing something to the younger self will have an impact on the future self. Looper takes this even further, by having memories change as well. So as Old Joe (Bruce Willis) watches his younger self (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) do things that will change his personal history, his memories alter and begin to overlap. The two timelines become superimposed in memory.

The Looper idea of altered memory is particularly intriguing. It implies that there is one timeline rather than many, and that the timeline is constantly integrating changes as Loopers flee or otherwise alter history.

Logic Problems:

The movie rather gruesomely shows what happens when a younger version of the self is tortured and maimed in order to catch a future version of the self. In one scene in particular,  the older version of a ‘Looper’ trying to escape a mob boss experiences his nose, fingers, then arms and legs disappearing as his younger self has limbs amputated by a physician. The problem here is: if the younger version has his legs cut off, how can the older version ever run?

the older version of a ‘Looper’ trying to escape a mob boss experiences his nose, fingers, then arms and legs disappearing as his younger self has limbs amputated by a physician. The problem here is: if the younger version has his legs cut off, how can the older version ever run?

Apparently it gets more problematic than this. After writing this article I found this, which raises a far more serious problem, suggesting that the Big Bad – the Rainmaker, logically could never exist. There’s also an excellent article on Looper at the Huffington Post, but fuck linking to a rag that doesn’t pay its writers.

The Terminator

Is a fine example of a predestination paradox. The Machines send a Terminator back in time to kill Sarah Connor, the mother of John Connor, the resistance leader who defeats  the Machines. The Machines only had time to send back one Terminator before the time-machine is captured by the rebels. This sets in motion a series of events where the resistance sends back a soldier (Kyle Reese) to protect Sarah; Kyle and Sarah fall for each other, and she becomes pregnant after a night of hot-and-sweaty, cut-to-silhouette of the bump and grind. Later, she gives birth to John Connor.

the Machines. The Machines only had time to send back one Terminator before the time-machine is captured by the rebels. This sets in motion a series of events where the resistance sends back a soldier (Kyle Reese) to protect Sarah; Kyle and Sarah fall for each other, and she becomes pregnant after a night of hot-and-sweaty, cut-to-silhouette of the bump and grind. Later, she gives birth to John Connor.

The rule for this version of time travel is simple: time is not changeable. If you can travel in time, whatever you do in the past will only contribute to making a present that is exactly the same.

The first film, as such, is not about ‘no fate but what we make,’ as Sarah Connor says in the second film (and becomes a motif for the series as a whole). In the first film there is only fate, immutable.

The second film allows for a divergence in the timeline, and the most recent Terminator (Genysis) allows whatever rules are required to fuck over the best film of the entire franchise.

In answer to your question: yes, Terminator is superior to Terminator 2. Any Terminator movie that requires THE TERMINATOR NOT TO TERMINATE ANYONE ON THE ORDERS OF A WHINY 13-YEAR OLD is a fucking stupid capitulation to the Hollywood rules of vanilla filmmaking.

Logic Problems:

The first film manages to tie itself off in a neat little bow, as anything the protagonists do, by definition, will only contribute to creating the present reality. So the original timeline stays intact: Doomsday still happens, but the humans still win the war. The paradox is baked into the timeline.

Logic becomes harder sustain in the Terminator series once it starts breaking its own rules. In Terminator II onwards the Machines try to stop the humans winning again, humans try to stop Doomsday completely, and each outcome is now possible (and, to be fair, the writers had to change the rules of time travel so there could be sequels).

Thus, instead of Sarah Connor living in Mexico waiting for nuclear Armageddon, as the second film begins she is inexplicably back in LA in a mental institution. In T2 and T3 the Machines send only one Terminator back in time, even though there doesn’t appear to be a reason they can’t send back squads of 20 or 100 under the new rules, and the latter films ignore the time-machine rule that only flesh or flesh-covered beings can be sent back (Terminator Baddy 2 is liquid metal only, Terminator Baddy 3 is liquid and hard metal only). Things make less and less sense as additional sequels are shoehorned into the timeline.

The Infinite Man

Rather than dwell on the time travel rules of this film, I’d rather recommend it as the best  time travel movie you haven’t seen. An independent Australian film made with a tiny budget, it unfurls loop after loop as the protagonist tries to win his girlfriend back. It’s clever, it’s funny, it keeps the viewer guessing, and it manages multiple loops without everything becoming a disjointed mess.

time travel movie you haven’t seen. An independent Australian film made with a tiny budget, it unfurls loop after loop as the protagonist tries to win his girlfriend back. It’s clever, it’s funny, it keeps the viewer guessing, and it manages multiple loops without everything becoming a disjointed mess.

I’ve included it here as a very watchable film that is a must-see for any time-travel aficionados.

Conclusion

In case you were wondering, the grandfather paradox is pretty straight forward. In this scenario, if you go back in time and kill your grandfather, logically you can never exist. But if you don’t exist, you cannot go back in time to kill your grandfather. But if you don’t kill your grandfather, and he therefore exists, why can’t you go back and kill your grandfather?

As for ‘six-dimensional time-travel’ – well, I still don’t know what the fuck that is. I did find a website devoted to ‘time travel philosophy’ explaining multi-dimensional time, which is certainly worth a look to the interested.

Time travel is a fascinating subject, whether about weighty issues such as free will vs. fate, or as a parable on unintended consequences, or the intellectual stimulation of unwinding a Gordian knot of paradoxes, or just the plain old satisfaction of playing with history.

I finished the draft of my time-travel story, confident I’d managed to pull off an original tale using alternate timelines and changeable histories in a way that was still logically tight. But with the way time travel works, I’m sure a reader could pull at one narrative thread and the whole thing would unravel.

And if they do, well, I’ll just tell them: “shut the hell up – I’m working in SIX DIMENSIONAL time.”